Climate Disarmament: analysis and possible actions from the Trento Conference

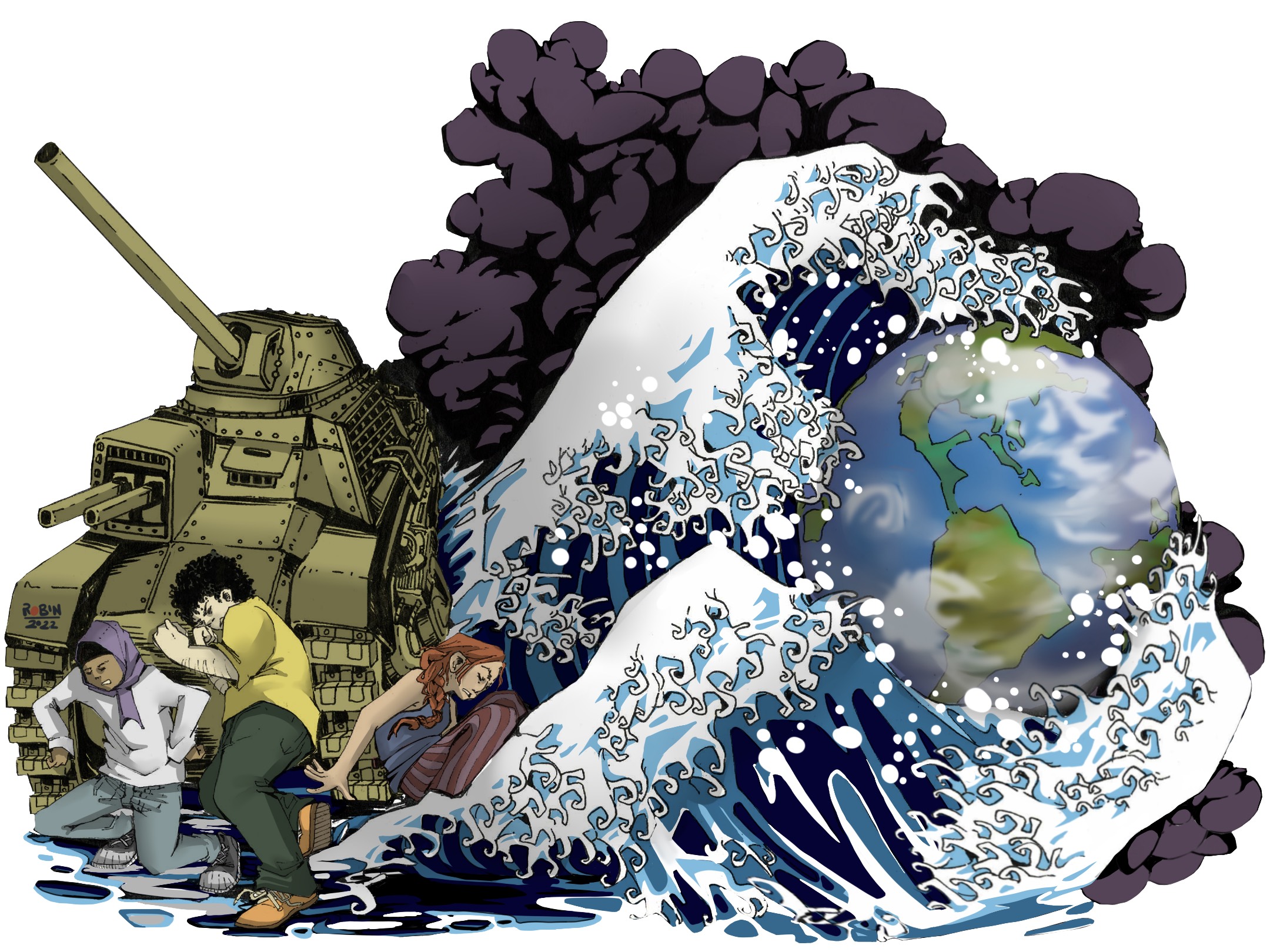

The three-day in-depth discussion concludes. The impact of militarisation policies on climate and environmental emergency, the relationship between climate change and conflict and energy transition the three macro topics.

The impact of militarisation policies on climate and environmental emergencies, the relationship between climate change and conflicts and energy transition were the three macro-themes tackled on 28 and 29 October during the days dedicated to Climate Disarmament in Trento, organised by the Italian Peace and Disarmament Network, the 46th Parallel Association and the Trentino Forum for Peace and Human Rights and in collaboration with MUSE and the Trentino Agenda 2030 Provincial Environmental Protection Agency, in the Representation Hall of the Regional Council of the Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol Autonomous Region. Conference preceded by a public evening at the MUSE Science Museum.

The first session, moderated by Roberto Barbiero of APPA Trentino, was focused on pollution, war and military industry. “There is,” explained Pere Brunet of the Centre Delas, “a vast network of global interests and power, led by a handful of supranational private actors that have undemocratic control over companies and governments. An industry, the military one, deeply polluting. ‘War and war preparation,’ he continued, ‘are fossil-fuel-intensive activities. Since 2001, the US Department of Defence has consumed 77-80% of its total energy. With the emissions associated with its activities and those related to weapons production, that comes to 212 million tonnes of emissions in 2017’. Emissions that are however difficult to count, because states do not report them. “Neither the armed forces, nor policymakers, nor civil society really know how big military emissions are. This is a huge blind spot in our global plans to tackle the climate crisis” added Ellie Kinney of CEOBS.

Emissions that are however difficult to count, because states do not report them. “Neither the armed forces, nor policymakers, nor civil society really know how big military emissions are. This is a huge blind spot in our global plans to tackle the climate crisis” added Ellie Kinney of CEOBS.

With Greenpeace journalist Sofia Basso we returned to Italy instead. “In spite of the effects of gas and oil on the climate crisis and peace,” she explained, “our country allocates about 70 per cent of its spending on military missions to fossil fuel operations, i.e. EUR 870m in 2022. Moreover, two of the national missions have as their first task the protection of Eni assets in international waters. This is also true for the European Union, about two-thirds of EU missions are related to fossil fuels”.

Cause-and-effect warfare and action for climate justice was discussed in the second session, moderated by Alice Pistolesi of the Atlas of the World’s Wars and Conflicts. States are reacting to climate change with militarisation. “Action is being taken” said Nick Buxton of the Transnational Institute, “to prepare for a militarised future, predicting that climate change will create a world of scarcity that will require security. This is based on the idea that resources will be limited, that this will cause conflict, and that armed and security forces will be needed to manage them. Climate change is used to justify increased military spending, rather than the other way around. This attitude is also reflected in the borders. It is very evident that many national plans focus on the ‘threat’ of migrants”.

Climate insecurity can therefore be an engine of conflict and profound injustice. “We have to consider, for example, the decrease in agricultural production,” said Marzio Marzorati of Legambiente, “and the intensive use of land that leads to desertification, degradation and the hoarding of fertile soils. Another issue is the economic calculation of natural resource depletion, which is now very difficult because economics does not take it into account. If a population depletes its mineral reserves, its forests, its soils, if its waters are polluted, all this does not enter into the calculation of economic productivity”.

Climate justice actions were discussed with Agnese Casadei of Fridays for Future Italy, a movement that managed to bring 8 million people to the streets in one year. “We have been questioning ourselves for some time,’ she said, ‘on how we can incorporate the pacifist cause into the environmental one, because we see the need for the two worlds to talk to each other more and more. Moreover, the movement was born in Europe but is trying to have not a western, but a global point of view”.

Transition towards climate security was discussed in the closing session, moderated by Daniele Taurino of the Nonviolent Movement. A transition that must not accentuate inequalities, both between and within states. “On a global level, the richest 1%,” said Gianluca Ruggieri of the University of Insubria, “is responsible for 23% of the increase in emissions, while the poorest 50% is responsible for 16%. One thing we have to take into account is that the transition cannot burden the weakest segments of society”.

Transition towards climate security was discussed in the closing session, moderated by Daniele Taurino of the Nonviolent Movement. A transition that must not accentuate inequalities, both between and within states. “On a global level, the richest 1%,” said Gianluca Ruggieri of the University of Insubria, “is responsible for 23% of the increase in emissions, while the poorest 50% is responsible for 16%. One thing we have to take into account is that the transition cannot burden the weakest segments of society”.

Agnese Bertello of Ascolto Attivo spoke about some examples of participatory climate action. “There are various useful and participatory methods to address these issues in a new way. Through public debate, deliberative polling, and assemblies, citizens are given a range of skills that allow for the development of effective proposals”. Participatory climate actions have been implemented in Germany, Italy, France and Great Britain.

But what role can law play when it comes to climate justice? Luciano Butti, lawyer and lecturer at the University of Padua, answered the question. “National law” he said, “can, for example, obviate the difficulties of international law by creating networks between technologically advanced states and states in economic and technological transition. It can, moreover, give a voice to those who do not have one and distribute the negative externalities not on the weakest groups”.